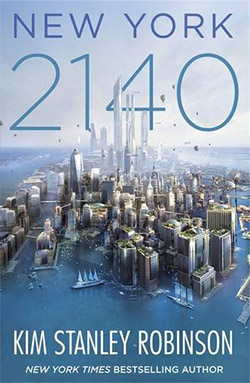

Not for the first time, and not, I can only hope, for the last, Kim Stanley Robinson takes aim at climate change in New York 2140, an immensely necessary novel as absorbing as it is sprawling about how that city among cities, so close to so many hearts, moves forward following floods that raise the seas fifty feet.

The Big Apple has been blighted. Uptown, being uptown both figuratively and literally, came through the crises brought on by humanity’s hard-to-kick carbon habit relatively well, but downtown, everything is different. Submerged, the streets between buildings are cast now as canals. Nobody has a car anymore, but boats are mainstays on the waterways. Pedestrians must make do with jetties, or walk the dizzying bridges between those skyscrapers that haven’t already collapsed after losing the ongoing fight to stay watertight.

Needless to say, New York as we know it is no more. But New Yorkers? Why, for good or for ill, they’re New Yorkers still!

There is a certain stubbornness in a New Yorker, cliche though it is to say so, and actually many of them had been living in such shitholes before the floods that being immersed in the drink mattered little. Not a few experienced an upgrade in both material circumstances and quality of life. For sure rents went down, often to zero. So a lot of people stayed.

Squatters. The dispossessed. The water rats. Denizens of the deep, citizens of the shallows. And a lot of them were interested in trying something different, including which authorities they gave their consent to be governed by. Hegemony had drowned, so in the years after the flooding there was a proliferation of cooperatives, neighbourhood associations, communes, squats [and such].

Robinson’s novel is arranged around a fitting for instance of this. The old Met Life tower on the drowned remains of Madison Square is home, now, to several thousand souls: a collective of individuals who all contribute to their cooperative’s pot—be it financially or by bartering man-hours or goods for common use.

Among the many are Ralph Muttchopf and Jeff Rosen, a couple of old coders, or quants, who live in “a hotello on the open-walled farm floor […] from which vantage point lower Manhattan lies flooded below them like a super-Venice, majestic, watery, superb. Their town.” But there are elements of their town that they deeply dislike, particularly the financial sector that has started gambling on what’s become known as “the intertidal zone,” and down-on-their-luck as they are, with as little left to lose as you like, Mutt and Jeff do something they shouldn’t: they hack the stock market.

That they’re immediately disappeared is hardly a surprise. What is surprising—to their disappearers at least—is that their vanishing act doesn’t go unnoticed. In fact, the delightfully disparate community that took Mutt and Jeff in when times were tough quite come together in an effort to find them, and those that took them too.

Taking the lead is Charlotte Armstrong, tireless representative of the dispossessed, and a board member of the Met Life coop. She clues in Inspector Gen Octaviasdottir, who investigates the quants’ disappearance in her own, old-fashioned way. Some suspiciously missing CCTV footage leads that latter to speak with Vlade Marovich, the sweetheart super of the skyscraper, and rather a magnet insofar as it’s he who attracts all of New York 2140’s other characters.

Initially, he only tolerates Franklin Garr, the Wall Street wunderkind who’s finally looking into doing something decent with the hedge fund he manages, if only to impress a pretty girl. But as a former father himself, Vlade’s interest in Stefan and Roberto, a pair of parentless preteens determined to dredge the sunken city for treasure, is markedly more paternal. And both last and least, he has a soft spot—like most men and many women do—for cloud superstar Amelia Black, famed for flaunting her figure first and secondarily for her efforts to save endangered species aboard the Assisted Migration airship.

At six hundred plus pages, New York 2140 is somewhat short on plot for such a long novel, but it’s absolutely, positively packed with characters rife with life, and every one of the above number has a part to play in the metaphorical and indeed the meteorological storms that follow. Some parts seem less significant than others—though she proves pivotal in the last act, Robinson struggles to make Amelia especially relevant—but every figure in the fiction eventually impacts every other, and that’s very much to the author’s point that “individuals make history, but it’s also a collective thing, a wave that people ride in their time, a wave made of individual actions.” Actions like Amelia’s.

Robinson’s tremendous investment in the trials and tribulations of these dissimilar individuals means there’s no small amount of satisfaction to be had as characters little and large cross paths, and as the narrative threads we’d thought independent—inconsequential, even—gather into something greater because they’re suddenly something shared.

There’s plenty of pleasure to be taken, too, from the nameless citizen whose “expository rants” restrict Robinson’s ever-present predilection towards “info dumps (on your carpet)” to snappy, standalone, skip-’em-if-you-can’t-stand ’em chapters. I wouldn’t recommend it, however. Just as the text’s many embedded perspectives give readers a sense of the setting from the inside looking out, said citizen’s potted histories help to build the world of this brilliantly ambitious book from the outside looking in.

And what a world it is! You see, for all that its premise rests on events that left billions dead or at best dispossessed, New York 2140, like the singular city at its centre when “the sun tilts to the south” in September, is ultimately optimistic:

Yes, autumn in New York: the great song of the city and the great season. Not just for the relief from the brutal extremes of winter or summer, but for that glorious slant of the light, that feeling that in certain moments lances in on that tilt—that you had been thinking you were living in a room and suddenly with a view between buildings out to the rivers, a dappled sky overhead, you are struck by the fact that you live on the side of a planet—that the great city is also a great bay on a great world. In those golden moments even the most hard-bitten citizen, the most oblivious urban creature, perhaps only pausing for a light to turn green, will be pierced by that light and take a deep breath and see the place as if for the first time, and feel, briefly but deeply, what it means to live in a place so strange and gorgeous.

New York 2140 is available now from Orbit Books.

Niall Alexander is an extra-curricular English teacher who reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for The Speculative Scotsman, Strange Horizons, and Tor.com. He lives with about a bazillion books, his better half and a certain sleekit wee beastie in the central belt of bonnie Scotland.